The national costume, however, is not just a certain type of festive garb: it is an expression of a nation’s sense of beauty, ability to form an ornament and put together colors, as well as knowledge of the craft. It embodies centuries-old traditions of making, adorning, and wearing the costume.

The Latvian national costume is a composite of a variety of festive outfits. There are many local varieties that are combined based on the five cultural-historical or ethnographic areas of Latvia: Vidzeme, Latgale, Augšzeme, Zemgale, and Kurzeme.

It is possible that at the basis of the older, barely determinable distinguishing marks of the traditional costume are the outfits of Baltic tribes and Livs living in what is now the territory of Latvia. Yet in every historic period the various costumes have shared many features in common.

The costume has changed over time, retaining something of the old and supplementing the new. The peculiarities of the costumes of a certain area became more pronounced over the long centuries of serfdom when the peasants were not moving around freely. The 19th century, particularly the 1860s also left their mark on the variety of the traditional outfits.

The basic element of the traditional costume is the shirt, which is an undergarment and an over-garment. Women’s shirts were long, coming down to under the knee and serving both as a blouse and a petticoat.

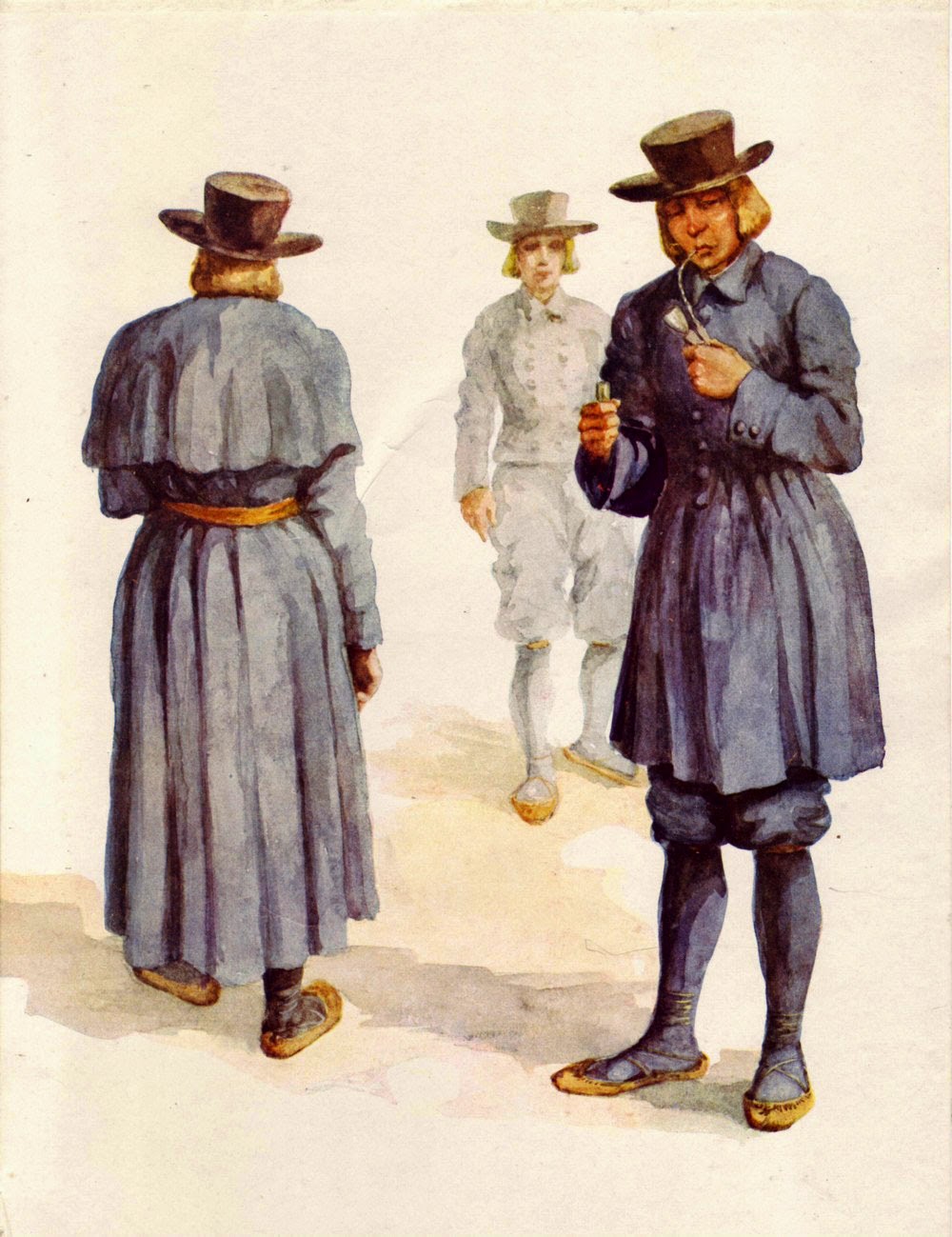

Over

the shirt, the women put skirt, bodice, jacket; whereas men wore a

vest and a short jacket or a longer or shorter overcoat.

Over

the shirt, the women put skirt, bodice, jacket; whereas men wore a

vest and a short jacket or a longer or shorter overcoat. The full outfit was not thinkable without a headdress: a crown for girls from their teenage years to the day of their marriage and a hat or a headscarf for married women; the men’s hat wearing was not so strictly regulated.

A part of the costume was also knit woolen or cotton lace socks and black flat heel shoes (in places – leather pastalas), for men sometimes boots.

The shirt was closed by one small brooch or several ones, the big brooches were used to keep the cape in place. Another element was the woven belts.

The Lielvārde belt is regarded as an outstanding example of a hand-woven adornment, a two-colored (red, white), patterned combination with the middle or the edges interwoven with a green or, more rarely, blue or purple thread, and with a variable motif (geometric pattern). Historically, its geographic distribution was Jumprava, Kastrāne, Krape, Laubere, Lēdmane, Lielvārde, Madliena, Meņģele, and Rembate parishes.

Although traditional belts from elsewhere in the country stand out with their rich ornamentation, only the Lielvārde belt has become the basis for a modern myth of the belt’s very ancient origins, the cosmic code that is written into it, and its special powers of protection.

In Latvian contemporary culture, the Lielvārde belt leads

its own independent, symbolic existence in people’s consciousness. Comparing the Lielvārde belt

ornamentation with other national and cultural patterns, Estonian graphic artist Tenu Vint raised

the hypothesis that this belt had preserved the information code of an

ancient civilization; that the story of the universe was inscribed

therein.

In Latvian contemporary culture, the Lielvārde belt leads

its own independent, symbolic existence in people’s consciousness. Comparing the Lielvārde belt

ornamentation with other national and cultural patterns, Estonian graphic artist Tenu Vint raised

the hypothesis that this belt had preserved the information code of an

ancient civilization; that the story of the universe was inscribed

therein.The Lielvārde belt was one of the most powerful symbols in the years of Latvian national awakening movement in the late 1980s and has not lost its importance even today.

The information that ornamented belts in antiquity were not used only as a personal adornment but also served to protect the wearer is found in a number of traditions, although that does not necessarily mean that the Lielvārde belt must have been a part of, for instance, a priest’s clothing. The scenario for the origins of the Universe read into the belt; the belt as a meditative system; as a yet untested piece of knowledge of the Universe may or may not be true: much will depend on what and how we want to see.

One thing is more or less clear, however: it is the Lielvārde belt that possesses a mythical power far beyond that of other belts and it is not because of the technology used in making it or because of its complicated patterns or beautiful colors, but because of its powerful symbolism.

Latvian folk-songs

Latvian folk-songs belong to the oral tradition that is much older than their first printed and hand-written records from the 16th-17th century.

They are characterized by several features that have been ascribed by researchers of folk poetry to an archaic poetic tradition.

One such feature is, for instance, the magical nature of the songs and their close relation to traditions: a great number of folk-songs represent "commentary on a ritual" with the purpose of structuring the ritual taking place in family events or other festivities and to explain the magic essence of the actions performed.

Another feature that is evidence of the age of the songs is the shortness of the texts, their structure, and the methods of stringing them together. E

ach quatrain in trochaic or dactylic verse is like a "snapshot" that expresses some observation, lesson, or feeling or describes some magical or practical act.

As they were being sung, the

texts were strung together in two ways: in tradition songs, in

accordance with the sequence of the ritual, in other cases, in

accordance with the theme, image, or a certain word.

As they were being sung, the

texts were strung together in two ways: in tradition songs, in

accordance with the sequence of the ritual, in other cases, in

accordance with the theme, image, or a certain word. Latvians also know songs that are made after the model of lyrical songs or epic ballads widespread in Europe, but the older foundation is the stringing of quatrains without developing a narrative and attaching them to one, narrow range melody.

Likewise, the contents of the folk-songs, dealing as it is with the everyday life of the peasant, is considered older than the theme of love. Their mythology is recognized as a good source of research into the archaic concepts of the Indo-Europeans.

RYE BREAD

The rye field blooms for two weeks, for two weeks

the grains mature and for another two they dry and then it’s time for

Jēkabs’s Day!

The rye field blooms for two weeks, for two weeks

the grains mature and for another two they dry and then it’s time for

Jēkabs’s Day!Jēkabs’s Day, July 25th, is the ancient new rye day when a loaf of bread made from the new harvest must appear on the table, everyone tasting a piece in respectful silence.

The newly baked bread was first presented for tasting to the head of the household, then it had to be tasted by everyone else.

In the old days, bread was baked in every Latvian country house. The mainstay bread, the daily bread was dark rye.

The bread was baked in a special oven and special

tools were used for the various stages of preparing and baking it. The

dark rye "rupjmaize" was baked of rye flour, the sweet-and-sour from

fine rye flour, on Saturdays karaša, a type of bread made of barley and

roughly ground wheat flour, but finely ground wheat flour was reserved

for white bread.

The bread was baked in a special oven and special

tools were used for the various stages of preparing and baking it. The

dark rye "rupjmaize" was baked of rye flour, the sweet-and-sour from

fine rye flour, on Saturdays karaša, a type of bread made of barley and

roughly ground wheat flour, but finely ground wheat flour was reserved

for white bread. Rupjmaize, literally "rough bread" is also called the "black bread". For making the dough a trough made of light wood was used. Usually, boiling water was poured over the flour; mixed with lukewarm water, yeast was supplemented by a starter from the previous baking.

The rather runny dough was left in the trough overnight to ferment. In the morning the kneading started. Kneading was hard but holy labor, so women who did it would put on a white shirt and put a white scarf around their hair.

The kneading took a long time, adding more flour and caraway seeds. When the dough would no longer stick to one’s hands the kneading stopped.

A loaf was formed, drawing a cross on its top, and then it was covered and left to ferment further.

Once the oven was hot, three pinches of flour were thrown in. If they

burned, the oven was swept with a damp broom made of leafy branches to

steam it up a little.

Once the oven was hot, three pinches of flour were thrown in. If they

burned, the oven was swept with a damp broom made of leafy branches to

steam it up a little.The trough with the dough was put next to the oven and little loaves were shaped on the baker’s peel that was covered with a dusting of flour or maple leaves and quickly put in the oven.

The sign drawn on the top of the loaf was usually a Christian cross, but sometimes older signs were pressed into the dough, pronouncing special spells.

A special tool was used to scrape the dough sticking to the sides of the trough and a small loaf was made of the dough. That was ready first and could be eaten by children and the bakers. A small ball of dough was left as a starter for the next batch. Sometimes a loaf was baked with a filling: sauerkraut with meat or pilchards, or salted meat with chopped onions.

The whole loaf was never given away for fear of giving away the good luck of the household. The first piece of the freshly baked bread was given to the head of the household who had tended to the crops, whereas the children and the young girls waited for the heels.

The cutting was started at the wider end of the loaf so that the older daughter would be married first and for the ears of rye to get bigger. The loaf was never left upside down, because there was the belief that the devil then can feed himself and send famine to the house.

JĀŅI

When the day is longest and the night is shortest,

at the summer solstice, Latvians celebrate Jāņi, St. John’s Eve,

staying awake around bonfires or burning barrels raised high on poles

so that singing, wandering neighbors can find the celebrations.

When the day is longest and the night is shortest,

at the summer solstice, Latvians celebrate Jāņi, St. John’s Eve,

staying awake around bonfires or burning barrels raised high on poles

so that singing, wandering neighbors can find the celebrations.Of the seasonal ancient Latvian celebrations, the summer solstice has most fully retained traditional activities that include preparations awaiting the great day and not only the festival itself.

There are local variations, myriad nuances, and different traditions handed down within families. In one period of the Soviet era the celebration was banned, in others organized; collective farms would organize collective Jāņi just as civil parishes and towns still do today.

People pick their venue, celebrating with their extended family, among friends, or at a public celebration – or trying to take in more than one as the long twilight turns into brief night.

In the Latvian farmer’s calendar, Jāņi marks the first haymaking and follows the beginning of astronomical summer.

Traditions in awaiting the holiday include the conclusion of spring labors, weeding, tending flowerbeds, learning folk songs, cleaning and tidying the home, making the special cheese in the shape of the solar disk, brewing beer, baking pīrāgi, and on the day preceding the festivities – decorating the farmstead with birch boughs, bouquets of flowers, garlands, oak branches and wreaths.

Scholars of religion connect Jāņi to solar cults and fertility rites, debating the extent of pre-Christian and Christian influences on the festival as we now know it. Those rites connected to fire, awaiting the sunrise, dancing around the flames and some other aspects of the celebration can be connected to a solar cult, but an ancient, phallic fertility cult is another root of the Jāņi traditions.

The birch boughs, the gathering of specific,

magical plants, the dancing around the fields and use of the boughs at

their perimeter to encourage fertility combined with the sexual

symbolism in folk songs and the root of the incessantly repeated word

līgo, which refers to swaying and swinging, make the erotic content of

the festival clear.

The birch boughs, the gathering of specific,

magical plants, the dancing around the fields and use of the boughs at

their perimeter to encourage fertility combined with the sexual

symbolism in folk songs and the root of the incessantly repeated word

līgo, which refers to swaying and swinging, make the erotic content of

the festival clear.Singing has a central place in the celebration. Many of the songs with the līgo refrain (leigū or rūto in the eastern region of Latgola) were originally sung by nubile girls, herders and ploughmen as they decorated the farmstead.

The sounds of nature, especially lovely in the long, mystical twilights of the northern summer, blend with the traditional songs, giving the celebration the unique atmosphere that makes it the most loved Latvian holiday.

St. John’s Eve is also known as the Day of Grasses. The brief summer is at the peak of bloom, different plants having their traditional uses in folk medicine, divination, as decoration and in the weaving of wreaths.

All guests are considered "children of Jānis," the host and hostess the father and mother of the "children."

Beer – especially home-brewed, smoky beer – and the special golden cheese are essential to the celebration.

No comments:

Post a Comment